This section is primarily intended as a resource for students. I regularly get asked to contribute to students research and often get asked questions I have previously answered or discussed in interviews and features. In response to this I have started to collate answers to specific questions divided into sections relating to projects, working methods, experiences or organisations I am involved with. Hopefully it will act as a helpful resource which I will keep updating as my practice evolves. (Where applicable I have indicated the year that I wrote the text.)

Advice

What advice do you have for aspiring photographers?

Always make work that is honest, that is a reflection of you. You should take pictures because it is something that you love to do and get enjoyment from. It could be that taking pictures helps make sense of your place in the world, or that it allows you to highlight a concern of yours, or lets people know how you feel. Don’t compare yourself to others, especially if it is negative and effects your self esteem. Don’t chase likes or base your self worth on what others think of you and your work. If you want to have a career as an artist/photographer you should be ambitious, work hard, although be prepared to fail and get rejected most of the time. I know it might sound contrived, but if you believe in what you are doing and you love it, that’s all that counts. It’s not easy making a living from photography, especially if you don’t want to work commercially, so be prepared to work lots of part time jobs as I have done over the last ten years!

…………………………………….

Influence

My work is always influenced by my life experience and multiple sources from contemporary culture, including Cinema, Literature, Painting, Photography and Television.

History

What's your story? How did you pick up photography and become interested in it?

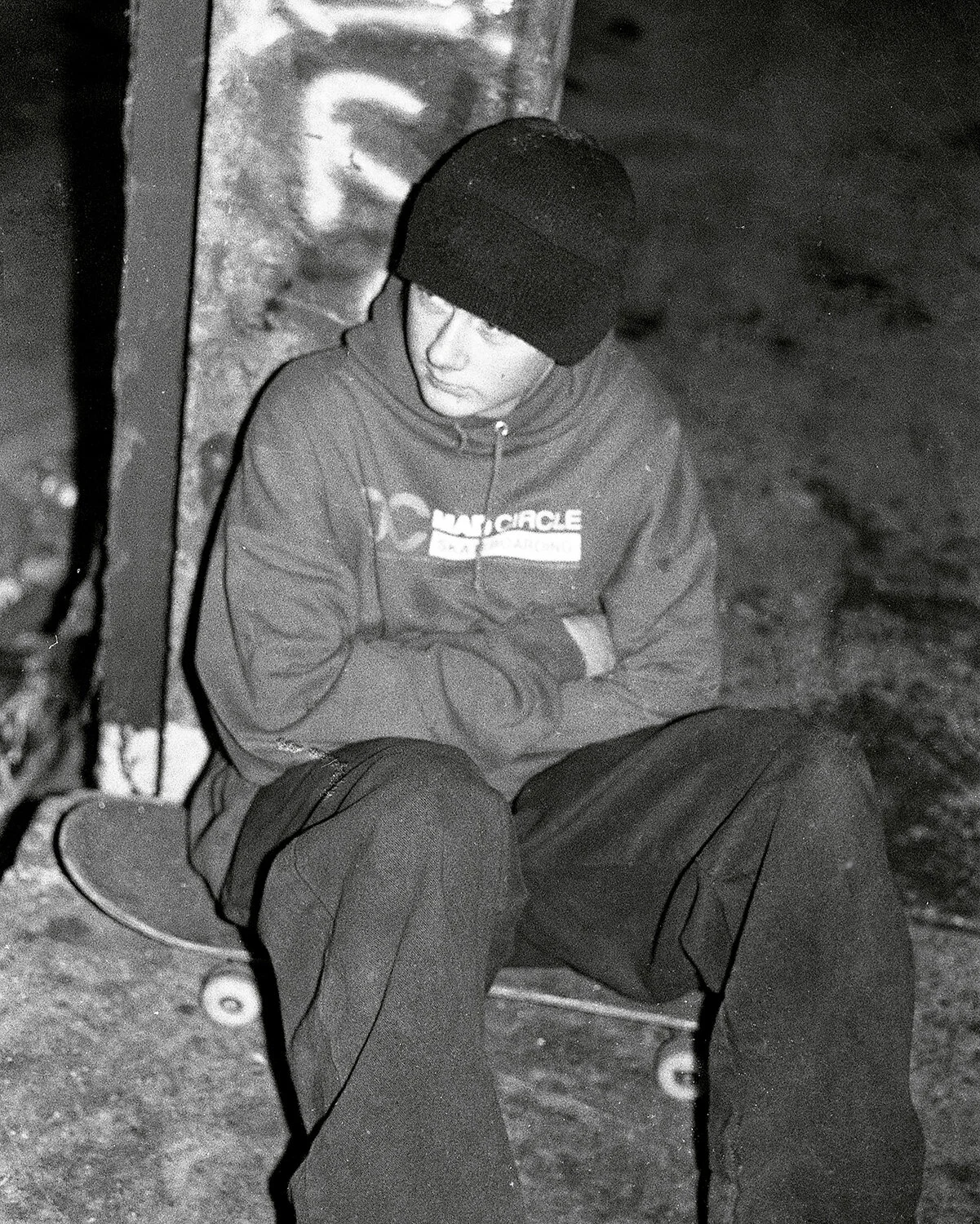

It's a long story, but I guess my interest was initiated when my Grandad gave me his old SLR. At that time I was heavily into skateboarding so I started taking pictures of my friends and that scene. I didn't take long before I also started taking photographs of the landscapes where I lived in the Midlands. At college I also did a City and Guilds qualification in photography which introduced me to the darkroom, then I was properly hooked. Even at a young age I realised how emotive photography could be in capturing a specific time and place and that really interested me.

After college I knew if I had gone straight to University I would have spent most of my time partying and skating, so luckily I was mature enough to realise I wasn’t ready to get the most out of a degree. Instead I spent the next 3 years working in factories and a large chunk of that time in a builders yard, which I loved, the hard manual work and being outside. I had applied to study Documentary Photography at Newport, and after seeing in the new Millennium I started there in the Autumn of 2000. I found it challenging at first, but knew I was in the right place. I was surrounded by lots of talented image makers and the no nonsense, honest teaching suited my personality. The degree introduced me to lots of varying practices, ideas and pushed my thinking.

Just before I was due to start my second year, I got rushed into hospital after having an attack/seizure. At the time I had no idea what had happened and it wasn’t until a couple of months later that I discovered they had diagnosed it as a transient ischemic attack (minor stroke). I spent 3 days in hospital and when I was released I still didn’t feel well at all. A month later I returned to University for my second year but I was really struggling to function and keep up with the programme. A couple of months later I received a diagnosis of glandular fever which at least explained why I felt so unwell.

Subsequently I deferred my final year hoping a year of rest would help. Sadly it didn’t and I felt more isolated and frustrated as my health wasn't improving. I completed my third year from home, only making it into University a couple of times. I had by this time received a diagnosis of M.E. or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, which is still a very misunderstood illness.

After finishing my degree my health fluctuated but I didn’t seem to be getting any better. In total this period lasted around eight years and it wasn’t until 2010 that I felt like I was returning to some kind of 'normality'. By now my parents had moved from the Midlands and had retired to Devon so I had to move with them as I was unable to support myself. Over the next few years my health slowly improved and I started working in Exeter, initially doing voluntary work. I had no aspirations to return to education, in fact, psychologically I had given up on doing any considered photographic work, feeling like that time had passed.

However there were two things that acted as the catalyst for me to re-engage seriously with photography. The first was that Jem Southam lived around the corner from me in Exeter, and one day I introduced myself to him when he came into the Art Centre I worked at. Whilst at Newport he was one of the few photographers that all three of my tutors included in their lectures and his sensitive landscape images had particularly resonated with me, his series, 'The Red River' is still one of my favourite photography books.

Around the same time I had started a relationship with a talented German photographer Jessica Lennan who was studying for her Masters at Plymouth University with Jem and David Chandler. Jem invited me to attend a few of their MA sessions and I also started going to the evening talks as well, and because of this I slowly started to re-engage with Photography.

Gallery of early work taken between 1994-1998

Robert, you’re originally from Birmingham and moved firstly to Wales and then to Plymouth to study. Geographically speaking, how much of an impact has leaving Birmingham had on the development of your photographic practice and career?

That’s a hard question to answer as my route to the present day hasn’t been particularly conventional, so I’ll give you a bit of a timeline first. I was born in the late 1970’s in Birmingham but then moved a little further south to Worcestershire when I was five years old to a small town called Droitwich, where I lived until leaving for University at 21 to study photography. After a year of University I became unwell (I will discuss this later) so moved back to the Midlands until relocating to Devon with my parents when I was 29. I was 34 years old when I returned to education, studying for a Masters in Photography & the Book and then an MFA at Plymouth University. It was during this period that I really created and developed my practice. However it’s slightly more complicated than saying it started then as if in a vacuum, as everything that preceded this return to education inherently informed the work I am making now. From my formative childhood experiences in the Midlands exploring the surrounding countryside, to the knowledge and history I gained from the documentary photography degree in Newport and the years I was ill, living my life vicariously through fiction, day dreams and films. I didn’t chose to move to Devon, it was fate and circumstance that brought me here, and yet had I not become ill I doubt I would be the photographer and person I am today. I wouldn’t have met my girlfriend Jessica who has been so supportive, or found myself living around the corner from Jem Southam. Both of them persuaded me to do the Masters, so leaving the Midlands has had a profound impact on my career, practice and life.

What about your studies? How your formal educational journey helped your skills and your awareness? Is there any professor you want to remember in particular?

I started studying Documentary Photography at Newport, Wales in 2000 and this was where my formal education began. It was exciting and I thrived in that environment, I am naturally competitive and enjoyed spending hours photographing and processing film in the darkroom. As most students can hopefully relate to there was a great sense of community, energy and expectation. The academic teaching was excellent, these were the days where the professors had to take slide photographs of images from books to include in their lectures, so it always makes me wince slightly at the sight of a pixelated image in a lecture now. Newport was proficient and professional and I always expect that now of others and myself. I looked up to Paul Seawright, Ken Grant and Clive Landen who were my main tutors at Newport and their work influenced my early practice. Alongside these primary influences the lectures at Newport were a great education in the history of photography. Aside from the American photographers, Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz and Joel Sternfeld I was really moved by Jem Southam’s work, it had a poetic depth that I wanted to try and express but wasn’t able to yet.

Later in life, fate and ill health meant a move to Devon and several years later I bumped into Jem and introduced myself, we lived five minutes walk away from each other. In 2013 I started studying for a Masters in Photography and the book with Jem as my professor in Plymouth and after that I completed an MFA with David Chandler as my professor. David has been really supportive in the development of my current practice and it has been invaluable to have someone whose opinion you respect to offer you advice.

At the age of 22, you were diagnosed with a minor stroke. You have talked previously about how your project ‘Vale’ is part of a nostalgic reinterpretation of summer, youth and the freedom associated with that difficult time, though seen through tainted eyes. Looking back, would you say that this period gave you an opportunity to reflect on your practice? or did you feel like you’d lost out on valuable time?

I started studying Documentary Photography at Newport, Wales in 2000 and this was where my formal education in photography began. It was exciting and I thrived in that environment, enjoying spending hours photographing and processing film in the darkroom. As most students can hopefully relate to there was a great sense of community, energy and expectation at Newport. Paul Seawright (http://www.paulseawright.com/), Ken Grant (http://www.ken-grant.info/) and Clive Landen were my tutors and their work and lectures really influenced my early practice. My final project in the 1st year was a series of images of a park in Newport, it was my first considered work about a specific place.

Just before the start of my second year I got rushed into hospital after a suffering a seizure, which was later diagnosed as a transient ischemic attack (a minor stroke). It was a terrifying experience and would affect me mentally for years to come. I didn’t recover from the TIA, I felt constantly weak, nauseous and dizzy and a couple of months later I was diagnosed with Glandular Fever and then a year later with M.E. or chronic fatigue syndrome. It took me four years to complete my degree, mainly working from home in the Midlands – as I was housebound for several years I turned the camera inwards making a subjective work about my situation. Initially this was a work about my own personal circumstances, which I then expanded for my final project, making contact with other young people suffering with M.E.

After completing the degree I no longer wanted to turn the camera inwards and as I wasn’t able to regularly get out to take pictures I didn’t make any considered work during my illness. However, whenever I could I took pictures as it is something I feel compelled to do. It was a hugely frustrating period of my life, I watched people I studied with finding their way in the world, winning awards and living their lives. I had no control over my own life and that was the hardest thing to accept.

It took close to a decade to fully recover from the illness and then overcome the anxiety of re-entering the world. In 2010 I moved from voluntary work into paid employment – working in the youth service and at an art centre. I was now living in Exeter and as fate would have it just around the corner from Jem Southam, someone whose work I had always admired. A year later I met my current partner Jessica (https://jessicalennan.com/), who was studying with Jem on the Masters at Plymouth and I would occasionally attend some of their Masters sessions and the visiting lectures in Plymouth. Both Jessica and Jem suggested I should do the Masters – I didn’t have a photographic practice at this point – I was doing some commercial photography work, but mainly filming and making documentaries for arts organisations. Psychologically I was reticent about returning to education and reigniting those aspirations I had at Newport, but I really wanted to start working on projects again and doing a Masters would allow me the time and opportunity to do that. David Chandler was really supportive during this period, specifically on the MFA; his advice was really beneficial especially when I was developing the Durlescombe project.

Those years of ill health were extremely hard, but that experience has taught me to accept adversity and also to learn how to be happy and content with life. I really appreciate any opportunity I now have and every achievement has added meaning for me.

Gallery of BA work taken between 2000 & 2003

Working Methods

What camera gear / editing setup do you use?

I work digitally, using a Nikon D850 in 5 by 4 crop mode. I treat it like a medium format camera only using fixed prime lenses. Most people assume I use film and often a specific camera, like the Mamiya 7 for example. I understand the romance of film, especially for younger photographers. I do still use film, occasionally taking pictures where I grew up on my Bronica, but I don’t share this work, it’s just for me!

I use Photoshop to edit work, although I aim to get everything right in camera, so there shouldn’t be much editing to do. Although over time my photoshop skills have got better. I don’t want people to see any process though, I like my work to feel natural.

There’s a healthy mix of portraiture and landscape within your projects. How do you approach each style differently and yet still make a series come together?

For me a project generally develops from an interest in a specific place or landscape. I always spend some time exploring, taking photographs and thinking to allow ideas to develop. It’s really important that I have an emotional response or feel a connection with a place before I can start thinking about working in that environment. I also don’t try and limit myself in terms of how the series can evolve; it could be a documentary project, a constructed series or a mixture of both. The constant is always the landscape and how people use and inhabit that space. In terms of bringing people into the landscape, it’s important for me that they feel like they belong within that environment. For a series like Durlescombe, that isn’t so hard as it is essentially a documentary project, and I am photographing people already in their natural environment. Whereas for my series ‘The Moor’, I chose all the people I photographed and put them in specific locations and situations. In these instances more attention has to be paid to how the people look and dress so that it feels like they belong in that space. I don’t particularly like photographing models or actors as they always try and give you something, a pose or a performance, so instead I just ask people I know, have met briefly or are friends of friends. Although the contextual situation of The Moor is fictional, it was important to me that I worked with people that had some relationship with Dartmoor, or that their personalities and lives offered something that complimented my constructed narrative for the project.

I think thats what drew me to your work initially. It's workings with portraiture and landscape images are mixed, with the clear lines of constrictive photography projects breaking away. What is it about working in the way you described that you enjoy so much?

There’s definitely a freedom in working this way that I enjoy, that I am able to construct and visualise a series of images is a real pleasure. It’s also quite a selfish act, possibly a lot of photography is. It definitely felt like a luxury to be able spend so much time on the moors, exploring and taking photographs. It’s a fine line though, between finding the time for self expression and earning money to pay the bills. Also, without sounding too much like a megalomaniac, having a level of control was really important, that I was able to dictate the subject and narrative was essential in creating a coherent series of images.

Would you say you have a signature visual language or pattern of concepts, if so, how would you describe this?

I definitely have specific areas of interest and so far all my work has been based in the South West of England, so it has a distinct geographical context. In terms of process the starting point for any project is my relationship to a particular area or landscape. I spend a lot of time exploring by car, on bike or foot to be able to get a sense of a place. However this perception of place is always influenced by my own formative experiences, nostalgia and inspiration from art, literature and film. Then there are specific elements that re-occur in my work, such as, history, youth, melancholy, beauty, the spiritual and the uncanny. In terms of a signature style or visual language people do say they can recognise one of my images when it pops up on their insta feed or if they see it on a wall. Which is really great, as there is so much work being made and if people can recognise and relate to what I’m doing then that’s lovely.

Your work involves many photographic landscapes. How important is the role of nature in your photography and why? How important are the people?

The landscape is integral to my work. All my projects are influenced by the landscape, it’s the starting point for ideas and then the work develops from there. For example my series ‘The Moor’ was a subjective response to the landscape and atmosphere of Dartmoor, Devon. Its otherworldly nature and bleak and barren landscapes felt like a dystopian environment, so that’s how that series developed. In the context of that project and my practice, the people are also integral. For ‘The Moor’, I worked with people I knew or had met in Devon. It was important to me that I selected people that felt like they belonged in that imagined world, although the work was fiction, it was important that it felt grounded and genuine, which I appreciate is a contradiction! For my series Durlescombe, again the initial interest was in the land nestling between Dartmoor & Exmoor in Devon, an in-between place. It was only after time exploring that area did the family connection to Mid-Devon became more apparent and I then started documenting the people living on and working the land. I would love to make a series just about the landscape, but every time I try and do this, it always feels like something is missing.

Robert you have mentioned previously that your practice is ‘motivated by the experience of place, in which the physical geography and material cultures of places merge with impressions from contemporary culture that equally influence perception’. Could you maybe elaborate on this statement, why is contextualising a personal response to place of particular interest to you?

The work you make as a photographer is always subjective and I think should be a reflection of yourself. My projects are almost always initiated by an emotional response to a particular landscape. This can be informed by memories of a similar place, or influenced by a book, film or piece of art, or often it’s a combination of both, memories which have blurred with contemporary culture. For example my series The Moor was influenced by my early impressions of Dartmoor as a child. My first memory was hearing hunting dogs baying on the moor when I was two years old. This memory and my early impressions of Dartmoor have since blurred with ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles (Book & Films), Famous Five books, 1970’s Children’s Film Foundation movies and latterly dystopian fiction. These are just some of the elements that informed ‘The Moor’, all contributing to an impression of ‘place’ which I then realised in the project. Interestingly the episode ‘metalhead’ (A dystopian story about killer robot dogs, filmed in gritty black and white) from the last series of Black Mirror was filmed in several of the locations I photographed for The Moor. I think working in this way captivates me as I am creating an environment and story from my imagination. I am also a slightly frustrated film-maker! So that’s why the series feels like it could be cinematic stills from a film.

Do you have any preference on cameras through the years? Do you use your phone for taking pictures?

I do use my phone and I can imagine in 25 years perhaps most young people will only really think of their phone as a camera. The Digital revolution has completely changed everything. At present I shoot on digital, using a Nikon D800, (Now D850) but shooting with a 5 by 4 crop. This camera completely changed everything for me and allowed me to move away from film. I use the camera much like I did the Mamiya 7, only using fixed prime lenses and very rarely checking the screen. There is a nostalgia about film, which I completely understand, but I can’t afford to work on film anymore, and as everyone thinks my work is shot on film, I don’t really need to. I see the camera very much as a tool, that enables me to capture something personal and poetic and if that image is caught on a digital sensor or on a negative doesn’t make much difference to me.

…………………………………….

Durlescombe

Durlescombe is one of your on-going projects. It is a mix of documentary-style imagery and archival images from Beaford Old Archive. Could you tell us a little about the project and why you decided to present the series in such a way?

I am using the conceit of this imaginary place/name, ‘Durlescombe’ to explore a lot of ideas. Primarily I am documenting the history and practice of working with the land and also examining my own attachment and family history related to this area in Devon. This includes my early memories from holidays and also this ‘other’, that which is carried with us from past generations. Fate brought me back to Devon and unbeknown to myself I began exploring places that directly related to my own personal family history. I feel a deep connection to Devon and the landscape and I am using Durlescombe to try and understand this relationship. My ancestors used to work the land, owning grain mills across Mid-Devon for many generations. Sadly there are no longer any working commercial mills, most have been knocked down, fallen into ruin or been converted into homes. So initially I made contact with threshers who process wheat to make thatch for houses, an old craft which hasn’t changed much in the last century. In the autumn a retired farmer I met whilst following the threshers invited me to watch him make cider. He used the left over wheat to sandwich the layers of apple to stack in the press. For me this connection between the wheat being harvested for thatching and processed in the summer and then used in the autumn for making Cider was a beautiful thing and told me a lot about working with the land.

Alongside these primary influences I am also creating a specific sense of place, one that is my own personal subjectivisation of a Devon that already feels slightly lost. I have a tendency to be nostalgic so I have tempered this with glimpses of modernity, and although I am interested in the rural idyll my wish isn’t to create a chocolate box representation of it.

When and why did the project begin?

Durlescombe grew out of an interest in the area betwixt the two Moors, Dartmoor and Exmoor. I was drawn to this landscape of wooded hilltops, narrow lanes, valleys, rural villages and patches of Moorland. I felt a real connection to the land and places I visited and I wanted to explore this attachment. I knew that my family name ‘Darch’ had links to Devon, as before I was born and during my childhood my Dad researched our family tree and traced our line back to the Norman Conquest in the 11th Century. Although as a kid if my parents were interested in something it was kind of like white noise to me, family history seemed pretty boring to a child. However on a damp Spring day in 2016 I found myself in a small town in Mid-Devon and thought it might be fun to see if I could find any Darch’s in the graveyard. Almost instantly and to my surprise I found a large gravestone with my name on it, Robert Darch. That was the starting point, that sense of a shared history of place, along with a developing interest in remnants of that history provided the catalyst for the Durlescombe project. I learnt that our relatives used to work the land, with many generations owning mills across Mid-Devon.

How long have you spent documenting it?

The first thing I should acknowledge is Durlescombe isn’t a real place; it is a fiction, a conceit to hold together ideas about identity, place and nostalgia. The photographs were all taken in Devon and the South West and the series is a layered assemblage of my documentary photographs, family history pictures, found illustrations and constructed imagery, both actual records and speculative fictions. I started working on the series in 2016 whilst studying for an MFA at Plymouth University and the work is still ongoing.

How has your experience of integrating into the community been? Have people been very open to the idea of you taking their photograph?

Around the same time I found the gravestone I stumbled across a factory where they were processing wheat to use as thatch and I asked if I could photograph the process. The foreman Martyn was really welcoming and I ended up following the threshers as they moved from farm to farm processing the wheat. On one farm I got talking to a retired farmer called John, it soon transpired that his wife was born a Darch and she had spent her formative years living at a Mill. This was a lovely coincidental meeting and John would subsequently invite me along to photograph lots of different rural activities he was involved with. They have both been really open and supportive and as I am still working on the project I still visit them for lunch, share work and discuss new ideas.

Are there any particular moments from the project that stick out to you?

As I mentioned I had spent some time exploring Mid-Devon before realising the ‘Durlescombe’ project. In one town I was passing through I spotted a derelict building tucked away behind some houses. I found a way in and began exploring the space. A fire had damaged some of the higher levels so I went down into the basement. Sprayed on the wall, was a quote from Kurt Cobain’s suicide note, “It’s better to burn out than fade away” except the paint either ran out at ‘fade aw….’ or they left it like that as a statement. It was a quote I knew well, I loved Nirvana and was 15 years old when Kurt died. I don’t know why but it felt like I was meant to be there and find that writing. I realise this might seem contrived, like when people tell you they’ve seen a ghost, but these moments in life, coincidences, déjà vu and signs feel important, that feeling you’ve been somewhere before and that you are meant to be there.

Three weeks later I found the gravestone with my name on it and after learning about my family history I realised the old building I had discovered was the mill my great, great, great, great grandfather and namesake, Robert Darch had owned. Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction.

How do you hope to portray the people or Durlescombe?

As Durlescombe is a fictional premise, an invented place, I made sure I communicated this idea to the people I photographed. I explained that they are more like characters inhabiting this place from my imagination rather than being an accurate portrayal of them. However, the majority of the images in the series are documentary photographs, that haven’t been directed or constructed by me. The atmosphere of the work is created by the people and places I chose to photograph and then sustained by the edit and layering of the work with found, archival and constructed images.

…………………………………….

The Island

What was the genesis (apart from the obvious) of your Brexit project?

In 2015 started taking pictures on Portland Island, a small island in Dorset, England, connected to the mainland by a road and causeway. The island is scattered with quarries, dramatic coastline, tunnels and imposing prisons. It has a peculiar, uncanny atmosphere, quite distinct from the mainland but with elements of Britishness, so really appealed to my sensibilities. My initial idea was to make some observations about the British nation, using this small island to reference the British Isles as a whole. This was of course well before there was any notion of Brexit happening, but I envisaged exploring a lot of the issues that led to the Brexit vote, immigration, poverty, etc. However the project didn’t evolve, most likely as I didn’t have any personal attachment or real passion for the idea, and aside from an interest in the atmosphere of the island I couldn’t envisage how the project would develop beyond that. My work specifically deals with attachment, feeling and emotion, to generalize, i’m a heart, rather than a head photographer and my initial idea for the Island was definitely a head led concept.

However, that’s where the title of the Island originated. Then a few years later when Brexit happened, I felt so heavy and sad about that decision, I just started taking pictures that attempted to visualize how I was feeling, which became a new version of The Island, photographed in the South West and the Midlands, where I grew up.

Most of my work has a slow genesis, often encapsulating older ideas and taking some time to realize the atmosphere or sense of place I am trying to create. Although The Island is a response to Britain voting to leave Europe, I was also drawing on feelings of melancholy I experienced in the past and how these emotions somehow felt heightened as a young adult.

Hello Robert, thank you for this interview. Please introduce your latest project The Island.

The Island is a poetic series of photographs made in response to Britain’s vote to leave the European Union.

The day we learnt that the United Kingdom had voted to leave the European Union felt like a tipping point to me, an event that preempted everything that was about to follow.

Later that year Trump was voted into office in the U.S.A. and now several years later in the United Kingdom we have Boris Johnson as our prime minister and another five years of conservative rule to look forward to. The Brexit vote and the outcome of that decision is highly complex and layered with a multitude of underlying sociological and political issues. The Brexit vote was the result of years of austerity, mass immigration, lack of job security, raised aspirations, greed, the class system, politics, neoliberalism, privatisation, fake news, indifference, social media and spin alongside a perceived lack of control over individual and collective fears. This is all now happening alongside a climate emergency, increasing overpopulation and a much more insular global society leading to a rise in right wing politics.

Why do you use an imagined approach, as opposed to a documentary one?

I am not a traditional documentary photographer, instead I work instinctively and use photography to capture a feeling or an emotion. I don’t like using the ‘A’ word as it feels slightly pretentious to me, but I do work more as an artist than a documentary photographer. Maybe I should just get over that hang-up and embrace it, buy some round glasses and a navy blue smock!

The Brexit vote and the outcome of that decision is highly complex and layered with a multitude of underlying sociological, political and psychological issues that make envisaging a documentary work close to impossible. Also if I did consider a documentary project about Brexit as a Pro European, I would start making judgements about certain elements and aspects of the British mentality that I can’t abide, and as an educated, white middle class man I can’t begin to imagine how I could do that without appearing judgemental and privileged in some people’s eyes.

Equally, i’m not so blinkered and idealistic that I can’t see and understand how this happened, why people would want to leave Europe, for the perceived safety and familiarity of good old Blighty. The Brexit vote was the result of years of austerity, mass immigration, lack of job security, raised aspirations, greed, the class system, politics, neoliberalism, privatization, fake news, indifference, social media and spin alongside a perceived lack of control over individual and collective fears…. I could go on.

Instead of trying to rationalize that I made a quiet series of images that reflect my own hopes, fears and aspirations for the future, combining melancholic landscapes with portraits of young adults, whom this decision will impact the most and (in general) they passionately want to remain part of the European Union.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to creating The Island, photographically speaking? What kind of images were you looking for in general?

I am not a traditional documentary photographer, so it’s not a literal response to the Brexit vote. I work instinctively and use photography to try and capture a feeling or an emotion and in this instance it's a personal response to what is a highly complicated and divisive political situation. I knew that I wanted to take portraits of young people as they will feel the effect of this decision the most, and in general there was a large divide in how people voted, with the majority of young voters wanting to stay in the European Union. I knew that I wanted to work in monochrome as it felt like the right choice for the sense of place and atmosphere I was imagining. In regards to the photos, I was looking for opportunities to take symbolic images that in context would allude to the situation and my feelings about it.

Who are the people you photographed? Are they simply young Brits or individuals who will be affected by Brexit? And was it intentional that you’ve only photographed young people?

The people I photographed are all young people from Britain. Everyone in Britain has and will be effected by Brexit whether they voted to leave or remain. It was intentional to only photograph young people as in general they overwhelmingly voted to remain in the European Union and as they are younger the effects of the vote will impact them the most over time. When I was in my late teens New Labour had just been voted into power after 18 years of Tory rule. Brit Art, Brit Pop and contemporary liberal British culture was being championed around the world. It felt like an exciting and positive time to be a young person, before the digital wave, fake news, Iraq war, climate crisis, diminishing resources and the impending end of days for large swathes of the animal kingdom and humanity.

How do you hope viewers react to The Island, ideally?

I think you have to make the work and take the photographs that fundamentally mean something to you, and if someone else shares in that experience and relates to them then that’s special. I am not a political campaigner and I don’t make work to try and change people’s minds. The Brexit vote is a very complicated and divisive issue. We live in a time where people appear to be fundamentally entrenched in their views, tribes, religions, politics and aren’t able to see something from a different perspective. People inhabit bubbles surrounded by individuals that feel the same as they do, a problem that has been exacerbated greatly by social media. I think this is wrong, preaching to the converted and not trying to understand or accept that someone else might feel differently and understand why this might be. I don’t have the answers, so instead I chose to make a quiet series of poetic images that reflect how I am feeling.

I hope this doesn’t sound too harsh, or cynical, but what’s the point of your Brexit work, what does it achieve?

I think you have to fundamentally make the work and take the photographs that mean something to you, and if someone else shares in that experience and relates to them then that’s wonderful.

I don’t make work thinking about what it will achieve, especially not in changing people’s fundamental views. I am not a political campaigner, that’s why I chose to make a quiet series of images that capture a subjective mood about a specific time, rather than add to the chatter around Brexit.

We live in a time where people appear to be fundamentally entrenched in their views, tribes, religions, politics and aren’t able to see something from a different perspective. People inhabit bubbles surrounded by collectives that feel the same as they do. This has definitely been reinforced by social media, witnessing people deleting friends if they were pro Brexit for example.

There’s an arrogance about believing that your viewpoint or opinion is correct and a safety and security in surrounding yourself with people that think like you do. I am sad about (Possibly) leaving the EU, but I am also sad about how divided and less empathetic humanity appears, something I am guilty of too.

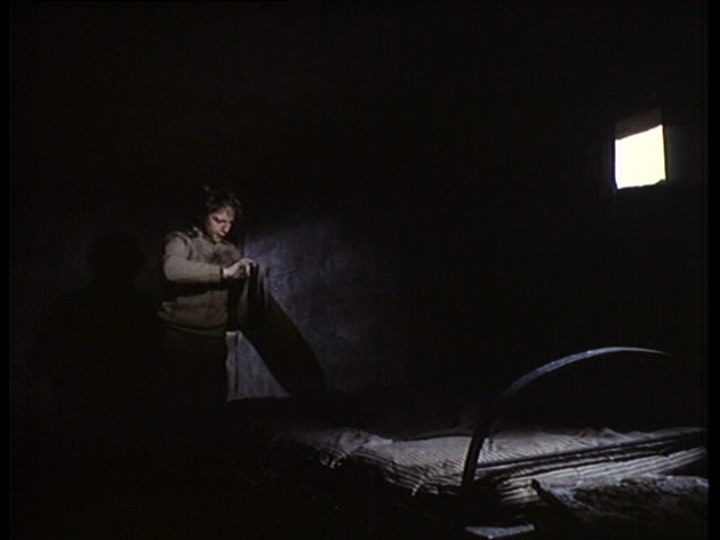

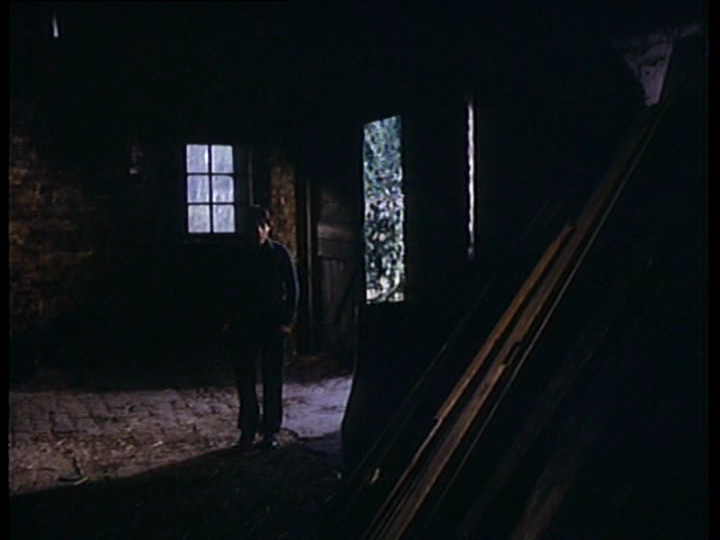

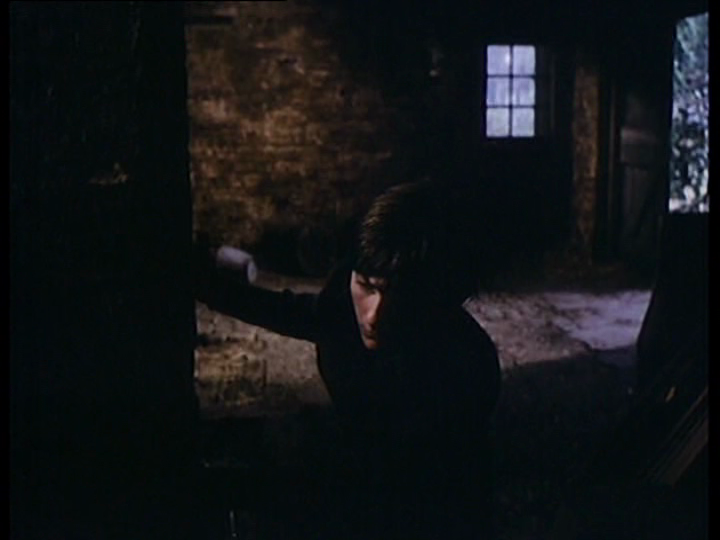

The CFF Film Black Island a visual influence and reference for The Island

…………………………………….

The Moor

What initially drew you to the moors of Dartmoor and Bodmin?

My first conscious memory was the sound of hunting dogs baying on the fringes of Dartmoor. At that time we lived close to Tamworth, just north of the West Midlands conurbation. Although our 1960’s semi backed onto fields, the rurality of Devon and the baying hounds must have appeared other-worldly to me as a three year old.

Over the course of my childhood we would continue to holiday in Devon and Cornwall, often passing over the Moors as we travelled further south. In the late 1980’s we visited some distant relatives who owned a farm on the edge of Dartmoor. Nestled in a valley, the farmhouse was in the shadow of the high moor, surrounded by tumble down barns and wooded hillocks. I spent the day exploring with my brother and the farmers children, excited to have the freedom to do so. As the years passed the memory of that day has since blurred with stories I once read, making it harder to distinguish between the experience and fiction.

In 2008 life circumstances forced me to relocate to Devon and a few years later I moved to Exeter, fifteen miles from Dartmoor. The Moors had always played an important role in my imagination and now I found myself living close to them. As a child we never stopped on the high moors, it’s apparent bleakness holding no interest for my parents, yet it was this barren, wild landscape that sparked my imagination. The Moors can appear serene and beautiful on a summers day, but during the winter, covered in snow, fog, battered by high winds and stinging rain you can lose yourself in the landscape.

Could you tell me more about the dystopian future you have constructed? What happens in this world, who lives there etc?

I took inspiration from literature and cinema, particularly, ‘The Road’, by Cormac McCarthy. The novel (and subsequent film) follows a father and son eking out an existence in a dystopian future. The cause of the dystopia in the Road isn’t defined in the writing and this idea really interested me. I wondered if I could do something similar with a photographic series. The advantage of a novel is that you are able to explain your ideas, develop characters and create a clearly defined narrative. So instead of trying to replicate this I focused on creating a specific sense of place and a sustained unsettling atmosphere.

This narrative is then reinforced by the reoccurrence of unnamed characters, often appearing on edge, in peril or distressed. The inherent wildness of the landscape heightens this fragile sense of existence, with the suggestion of an unseen presence adding to the isolation and tension. The cause of the dystopia isn’t defined in The Moor, but the lack of obvious technology and the use of primal elements (like fire) suggests a breakdown in civilization.

And what sort of research (if any) you did that pushed you to create the images you did, particularly with the Moor as it’s very much that atmosphere and meaning that inspires my project!

I spent some time researching the history of Dartmoor in contemporary culture, including literature and cinema. Alongside this I read a lot about Dartmoor, researching its history and myths and legends associated with it. In terms of visual research the work is influenced by cinema and television, in particular 1970’s and 80’ horror films by directors Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, Tobe Hooper, Sam Raimi & John Carpenter, and also an obscure British Children’s Film Foundation movie called Black Island (There are some clips on youtube). I saw Black Island when I was 6 or 7 years old and it had a profound impact on me. The acting isn’t so great now, but thematically and visually you can see where I took a lot of influences from for The Moor and my other work. It also manages to create a believable sense of place and atmosphere.

The concept of memory and place, how the moors have shaped part of your upbringing comes through within the work. There is certainly a meditative state. Images which repeat themselves, zoom in, subject looking like they are in a day dream. Besides your own personal relation to the moors, what other influences did you bring to the project?

Initially I was planning on making a more ‘conventional’ series of photographs about Dartmoor, referencing its history, myths and place in contemporary culture. However, after spending some time on the moor I soon realised what really motivated me was how being in that environment affected me emotionally. So instead of focussing on the literal, I started making images that were less tangible. The sense of place I derived from the moor inspired me to create a fictionalised narrative with a dystopian theme. This was in part influenced by the novel, ‘The Road’, by Cormac McCarthy and as a response to the perceived uncertainty of life in the modern world.

Before starting the Masters at Plymouth University in 2013, it had been close to a decade since I had last completed a series of images. So this period was instrumental in terms of establishing a practice again. I hadn’t worked so narratively before, or constructed imagery, so it was particularly interesting how this developed. There is also a definite influence from cinema in the aesthetic visualisation of the series, though not one specific reference, instead a series of visual vignettes collected over time.

How did the real landscape of Dartmoor inspire this?

Initially I considered making a documentary project about Dartmoor and the people that inhabit and work on the moor. However, I soon realised that I was far more interested in making a work about how the moor made me feel. It’s definitely a beautiful landscape, but it’s also harsh, barren and bleak, especially in the winter. When the moor is cloaked in low cloud and fog the landscape feels otherworldly, apocalyptic and empty and makes me feel lost, alone, isolated, excited and scared.

I grew up in the midlands but we would visit Devon on family holidays. On one occasion we visited distant relatives who owned a farm on the edge of Dartmoor and this formative experience had a profound impact on me. I recently discovered a short story I wrote for school when I was twelve and it’s uncanny how (without knowledge or memory of writing this when photographing The Moor) I was drawn to the same visual representation of Dartmoor. Here’s one line from it that is particularly resonant. ‘The window downstairs was open and he looked over at Dartmoor, the sun rising slowly behind it, it was a cold lonely place.’

What mythology is referenced in the project?

Dartmoor has a long history with plenty of local myths connected to the landscape and specific places on the moor. There are the infamous hairy hands which are said to appear floating in front of people and of course the legendary Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle which was inspired by the story of Richard Cabell who died in the 1670’s. The ancient druids of Dumnonia (4th to 8th century Devon) worshipped many gods, including Belus (the sun). It was commonplace at the time to make gods of everything that was capable of doing harm or integral to human existence. It is suggested that Bellever & Belstone on Dartmoor are named after Belus, the sun god. I specifically reference the sun and the light from it in The Moor, drawing on this ancient history and suggesting the sun could possibly be something that should be feared. I also reference more universal mythology in The Moor, like a lone figure walking into a dark forest, or a lone disheveled figure struggling to walk across the moorland landscape. This lone figure is a classic archetype, typified by the escaped convict roaming the moor in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

How did the moors make you feel whilst working on the project? There are certainly cinematic moments which burst through the projects seams, the portraits in particular help to narrate the work in terms of its fictionalised state. The faces look wild and confused, lost in the landscape that surrounds them. With 'The Road' in mind, did your subjects have the same reaction to the landscape you were placing them or did themes from the book take over in terms of the portrayal of each subject?

We don’t have much, if any, true wilderness in England. Yet, standing in the middle of Dartmoor, I certainly felt isolated and separate from the modern world.

My experience whilst working on the series was varied, influenced in part by the atmosphere of each place and the state of my mind. At times I was excited, inspired or scared.

I chose to work with subjects that already had an existing relationship with the moors. So, although the work is predominantly fictionalised, it was important for me that this narrative was grounded in a subjective reality. In terms of ‘The Road’, the main inspiration I took from the novel, was how Cormac McCarthy locates his characters in a dystopian world, yet offers no explanation for the cause of the dystopia. Obviously a photographic series allows much less space for narrative explanation and character development than a novel, so my aim was to focus on creating a specific atmosphere and sense of place for the characters to inhabit.

The subjects also had varied reactions to the moor, sometimes scared, in awe, or cautious. I had spoken with them about my motivations for the work beforehand, to make sure they understood what I was trying to achieve with the series. Though whilst out, I was occasionally guilty of using the perceived supernatural history and myths of Dartmoor to illicit a fearful response.

What kind of techniques and processes did you use to achieve the images you created? Did it take planning for each shoot and image or was it more spontaneous?

Every shoot was planned in terms of the location, weather and person I went out to photograph with. I spent a lot of time exploring Dartmoor, walking, driving and researching locations online that I felt would complement the atmosphere I was trying to create in the series. I would normally spend a whole day with my subjects, often walking long distances to locations. Although the project is constructed, on the days I was out with people I also allowed for situations to naturally present themselves. I have included a series of three images of one of the characters falling asleep leaning next to a fallen tree. My subject Guy hadn’t slept the previous night, he was partying and during the whole shoot he was literally falling asleep standing up. This was a genuine response to a set of real world circumstances which luckily fit beautifully with my constructed narrative of people inhabiting and surviving in a dystopian future.

With this project being ambiguous in its nature, with the strings of the work holding closely onto personal memory and literature, how did you find weaving the threads together? It's a harder thing to do than a straight up documentary project...

Yes, you’re right. With a documentary project you’re only working with what is happening in front of the camera, and in theory you have no control over those elements. The content dictates the work, rather than the photographer dictating the content. Although, at present, contemporary photography is more ambiguous, projects don’t always sit within the old generalisations of genre. I often see work that replicates the conventions of documentary photography, yet latterly discover elements were constructed, that liminality between documentary and fiction is much less apparent.

In terms of constructing this series, the initial point of interest was Dartmoor. After spending some time in the landscape, exploring, thinking and photographing, I began to develop an understanding of the atmosphere and aesthetic of the work. At this stage I started considering people to photograph, that I felt would compliment the narrative. After these elements were decided, the story began to develop. However, as I made more images, the narrative continually evolved, until all the influences combined to create the finished series. There was a lot to think about in terms of weaving the threads, but this is where the editing of the work played a crucial role in the construction of the narrative.

What do you hope to portray with the series?

The Moor particularly portrays the unease I feel about the uncertainty of life in the modern world. It feels especially prescient now with the country split over leaving Europe and years of tory cuts and uncontrolled capitalism which have created unsecure and unfulfilling work environments. Alongside global warming and the continued destruction of the natural environment it doesn’t feel like we are far off from a dystopian future, in fact it wouldn’t be too hard to argue for many they are already living in one.

……………………………

Vale

What is ‘Vale’ and what is the story behind it ?

Vale reflects on the long period of ill health I experienced in my twenties and the isolation and loneliness that happened because of that. Vale slowly developed over the course of a few years from an initial interest in the valley landscape outside of Exeter where I live. However I soon realised the work I was making was more layered and it became a cathartic exploration of those lost years. Whilst I was ill I would get lost in daydream and fiction creating imaginary worlds to temper the isolation and sadness I felt. This dreamlike imagery became integral to the atmosphere and aesthetic of Vale. A photographer recently said to me it felt like I was dreaming the pictures. Vale imagines a romantic summer, spent swimming in rivers and exploring woods. The people almost act as stand ins for me, a romanticised version of how my life could have been had I not become ill when I was so young. Their uneasiness reflects my sadness and creates a conflict between their youthfulness and the beauty of the landscape around them. I have always had an interest in the notion of ‘eerie’, that unsettling feeling you get when presented with something that you can’t understand or comprehend. From a fascination with ghosts as a child to horror films as a teenager, these formative experiences have really influenced the work I make. Vale is the most personal work I have made, which was one of the reasons I decided to self publish the work. I am really interested in publishing, which is why I created the imprint, LIDO to self publish my work and possibly the work of other artists in the future.

Vale' as you wrote « is a construct, part a reimagining of aesthetics and semiotics derived from contemporary culture and also a romanticisation of memory, hope, place and remembered landscapes.» I agree that somehow this series follows some precise aesthetic canons. Almost forces them, or puts them on stage. However, the merit of this project, and that is what has attracted me, is the fact that some of these images are able to convey feelings that are not always easy to describe in words. Photography has this force as the music to express universal conditions that we can not explain through a common language.

You have just described the beauty and power of photography, it’s ability to express something that I can’t in words, most likely because I don’t have that ability or that photography offers something else, it’s that unknown that is fascinating to me. The work you make as a photographer is and should be a reflection of you. Vale is the most personal project I have made, I am not that emotional as a person, but I am very sensitive and I can express this through my photography to offer some truth about myself.

I find 'Vale' to be your most impressive and insightful work. How did it grow within and took a physical form? Did it offer you some reconciliation after recovery?

Thanks, it is the most personal work I have made. Vale slowly developed over the course of a few years from an initial interest in the landscape outside of Exeter (where I live). However I soon realised the work I was making was far more layered and it was really a cathartic exploration of those lost years. Whilst I was ill, I would get lost in daydream, fiction and create imaginary worlds to temper the isolation and sadness I felt. This dreamlike imagery became integral to the atmosphere and aesthetic of ‘Vale’. The work didn’t offer any particular reconciliation, instead it allowed me to quietly contemplate that time of my life and explore the hopes, dreams and aspirations I had as a younger man.

Can you tell me a little about your relationships with the people and places that you photographed for Vale?

Like a lot of my projects Vale was formed from several different threads and weaved together to create a series. There was the initial interest in the valley landscape just outside Exeter where I was living. A landscape of rivers, woods and fields that was reminiscent of the Worcestershire countryside that I grew up close to. Before I started my Masters I had set up and was running a collective for young photographers, called Macula. Every Tuesday evening we would meet up and go and take pictures and explore, often in the valley outside Exeter. The collective allowed me to share in the experiences of the members, their energy and interest in the world. In one sense I was trying to recapture that feeling of being young and free, it made me reflect on those lost years. I naturally started photographing the members of the collective and in the context of Vale, they acted as stand ins for me, for my past life. Once the atmosphere and narrative of Vale was formed in my mind I started to arrange with friends to photograph them as part of the series. For example I organised a trip for three close friends, who were all about 10 years younger than me and about to leave for London at the end of the summer. We spent a day walking along the river, stopping to occasionally swim. For them it was about a change in their lives, in their early twenties on the cusp of a new adventure. For me it was also about friendship, adventure, the warmth of summer and that feeling of being young and content. The Places in Vale were landscapes I visited regularly, locations I had found in the Exe valley, close to Exeter right up to Exmoor in North Devon.

How do you achieve the look of your photographs and could you take us through the process?

For Vale I photographed in the Summer, often very early in the morning or in the evening, so dawn and the golden hour. The use of light is very important in creating a sense of place, which also helps reinforce the narrative of the work. The 5 by 4 frame is also important as it feels more constrained than 35mm. I wanted the images to feel like concise moments, like stills from a film. I took a lot of influence from cinema whilst making this work. The look is really created by the places and people I am photographing, romantic British landscapes with young beautiful people. However there is often something unsettling in their gazes, which creates a juxtaposition between them and that beauty. All the subjects in the pictures were people I knew, friends, work colleagues and members of a youth photography collective I had set up. I very rarely staged pictures, as I wanted the work to feel natural and not contrived. However I often orchestrated situations, for example organising a day when three friends walked along the river for a day, stopping occasionally to swim. Then amongst that, I captured images when they were presented to me.

Could you tell us the backstory of some of your photographs ?

Vale initially evolved over a period of time and was shaped by chance encounters, serendipity and situations I found myself in. In the early stages of making the series a friend asked me if I could take some stills of a short horror film he was making in Devon. He had some funding and had rented this old farmhouse that was due to be auctioned in a month, but the cousin of the old couple who owned it was still living in the house. All the interior images from Vale were photographed in this house. The room with the bed in it was where the old man lived and the final image of the series was taken in the living room of the house. It was an unsettling location and this early experience really reinforced the sense of eeriness which would permeate the series.

I normally develop series of images from several smaller shoots/stories which then provide a structure for the atmosphere and narrative of the work. Often this is reinforced by pure serendipity. Like the evening I found a chopped log on a ride in a wood that had a swarm of bees inside it. Or another evening when I went to the river and the sky was full of insects which were glowing in the warmth of the setting sun. Perhaps the most prothetic image was a photograph I took of a couple outside an abandoned house I had found on the edge of a small Devon village called Black Dog. On reviewing the images my eye was suddenly drawn to what looked like a figure in the window and as I zoomed into the image, a chill went down my spine, the figure appeared to have a face. The rational mind most likely attributes the figure to dirt and the way the light fell on the window. Either way, this figure felt prothetic and the appearance of it felt very fortuitous in the development of the series.

……………………